The Emergence of the Neo-Ottoman and Turkic World

In recent decades, Turkey has pursued an increasingly assertive foreign policy. This strategy is shaped by its imperial historical legacy, geopolitical challenges, and regional power ambitions. Ankara seeks to expand its influence in the Middle East, the Mediterranean, the Balkans, and Africa through military, economic, and diplomatic means. The “neo-Ottoman” foreign policy strategy and the “Blue Homeland” doctrine both reflect Turkey’s aim to establish a stronger regional role. These ambitions go beyond the regional level: Turkey is becoming an actor in global power struggles, posing challenges not only to its neighbours but also to great powers.

By Zoltán Egeresi and Róbert Gönczi

Turkey has long sought to increase its influence in the Middle East and North Africa, particularly in Iraq, Syria, and the Eastern Mediterranean. According to Zoltán Egeresi, a Turkey expert at the Institute for Strategic Defense Studies of the National University of Public Service in Budapest, “Turkish strategy is based on the so-called ‘neo-Ottoman’ foreign policy concept, coined by former Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, aiming to partially restore the spheres of influence of the historical Ottoman Empire.” Although the concept dates back to 2001 and Davutoğlu’s relationship with President Erdoğan has since deteriorated, Turkey still adheres to this approach. This strategy does not seek to resurrect the Ottoman Empire, but rather to build a zone of influence where Ankara plays a leading political, economic, and cultural role. Ankara also prioritises control over water resources and other natural assets, such as the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, which serve as strategic tools in diplomatic dealings with neighbouring countries.

Turkey also projects military power in its zones of influence. Ankara justifies military interventions not only in defence of its interests but also as contributions to regional stability, at least according to its narrative. Its interventions in northern Syria and Iraq, especially against Kurdish forces, have drawn significant attention. The city of Mosul is a strategic target in Ankara’s plans. Turkey also aggressively pursues control over maritime boundaries and energy resources, particularly in its disputes with Greece and Cyprus. In the Aegean Sea, Turkish air forces frequently violate Greek airspace and contest maritime borders to assert regional dominance.

Besides military tools, Turkey also uses economic and diplomatic pressure to increase its influence. This includes leveraging energy projects, migration policy, and water management to exert pressure on other states. Ankara extends its influence through economic cooperation and diplomatic ties, especially in the Balkans, the Middle East, and Africa. Over the past decades, Turkey has also placed increasing emphasis on cultural influence, promoting Turkic traditions through foundations and religious construction projects, such as mosque openings, to foster local sympathy.

The Besieged Fortress

The Turkish state mentality is complex and rooted in specific imperial aspirations. What historical, geopolitical, and domestic political factors explain its behaviour?

Historically, Turkey’s current state thinking is deeply rooted in the legacy of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Empire was a dominant power in the Middle East, North Africa, and the Balkans for over 600 years. This legacy still shapes Ankara’s geopolitical aspirations. The defeat in World War I, the empire’s collapse, and subsequent territorial losses – particularly under the Treaties of Sèvres and Lausanne – left a deep imprint on the Turkish political elite. This historical trauma continues to shape thinking not only among elites but also across Turkish society, often used to justify the leadership’s foreign policy moves,” explains Egeresi.

He adds that Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s radical modernisation policies in the 1920s created a centralised, secular, and strong state from the collapsing empire. Although the current leadership has partly moved away from Kemalist secularism, the principles of a strong state, military dominance, and nationalism remain key elements of Turkey’s political culture. The state often derives legitimacy from defending against perceived “external threats,” using national security arguments to justify geopolitical actions.

A series of historical conflicts has contributed to Turkey’s so-called “besieged fortress” mentality. “Political and military rivalries with Greece in the Aegean, with Syria, Iran, and Iraq in the Middle East, and with Russia and Iran in the Caucasus have all contributed to a persistent sense of threat,” confirms Egeresi. Situated in a region of intersecting Russian, American, and European interests, Ankara is forced into a constant balancing act while maintaining an autonomous geopolitical strategy.

President Erdoğan and the ruling AKP (Justice and Development Party) frequently reference the imperial past and the restoration of Turkey’s regional leadership in their rhetoric. Nationalism and Islamization are increasingly intertwined in Turkish society, fuelling a more proactive foreign policy and the expansion of regional influence. The ongoing conflict with Kurdish separatists and the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) also creates a constant internal crisis that the Turkish leadership exploits to consolidate power and stoke national sentiment. These dynamics help explain Turkey’s assertive and often confrontational behaviour on the international stage.

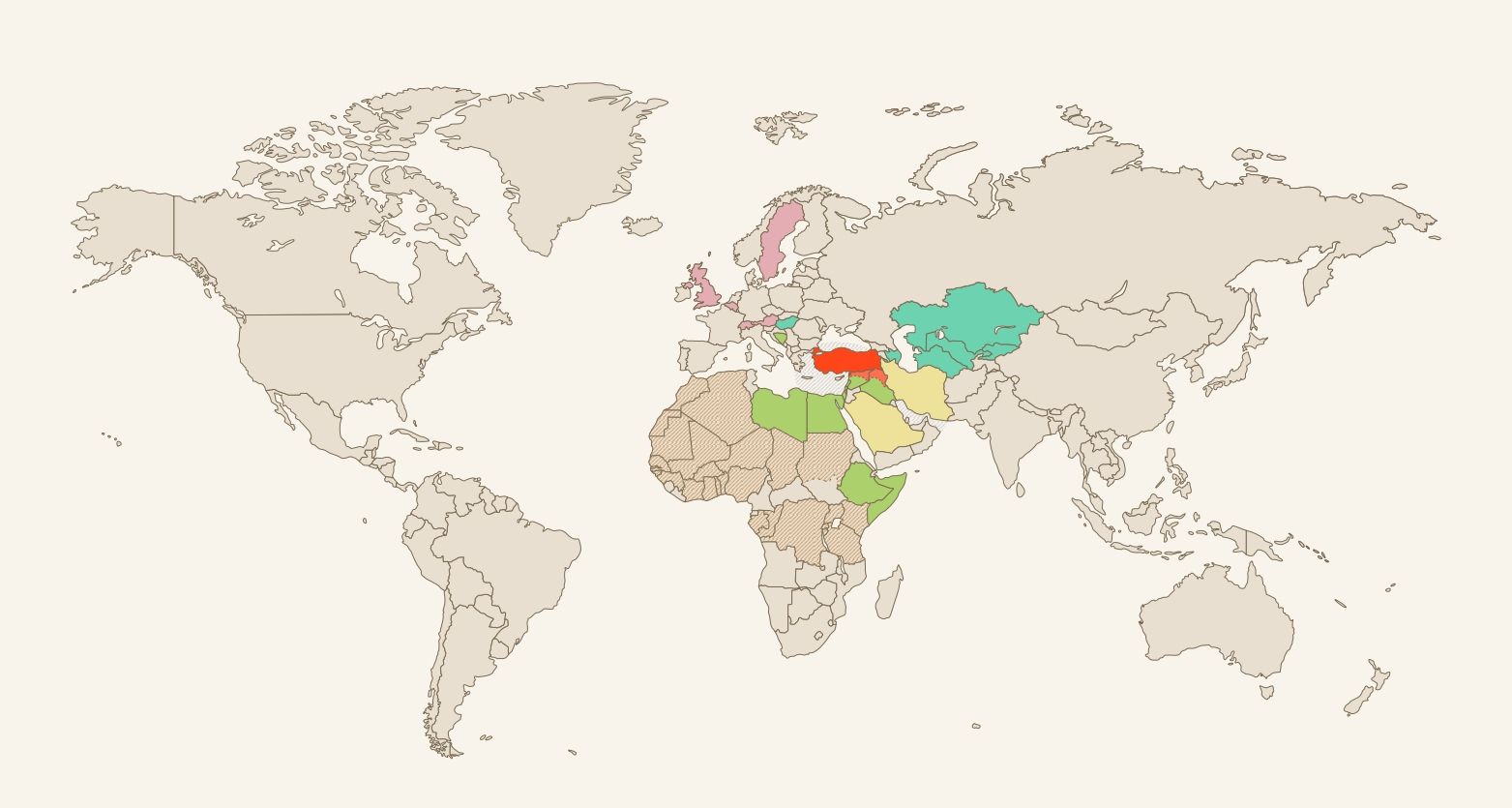

Red: Turkey

Light red: Areas occupied by Turkey

Gray stripes: Maritime areas of particular importance to Turkey

Benetton green: Council of Turkic States

Light green: Areas of Turkish interest

Yellow: Diplomatic relations of particular importance

Brown stripes: Military cooperation

Mauve: Areas with a significant Turkish population and Turkish political influence

The Blue Homeland

The Turkish military plays a key role in achieving geopolitical goals. Despite crises, the Turkish economy has shown resilience, and access to energy resources also significantly shapes state strategy. Ankara evaluates territorial claims and expansion plans in light of these realities. But where are these efforts directed?

For Turkey, maritime boundaries are not merely legal or economic issues, but strategic concerns tied closely to its sovereignty and regional status. Ankara makes increasingly assertive territorial claims in the Eastern Mediterranean, particularly around Cyprus. It does not recognise Cyprus’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) agreements with Egypt, Lebanon, and Israel and has unilaterally announced its claims. “Turkey aims to gain recognition for the status of the northern part of Cyprus, which they have occupied since 1979 and seeks a maritime deal with Egypt that would exclude Cyprus from regional energy cooperation,” adds Egeresi. In 2019, Ankara and Libya signed a memorandum of understanding on maritime boundaries, ignoring the rights of certain Greek islands such as Rhodes, Crete, and Karpathos.

Turkey continuously disputes Greece’s maritime and airspace rights in the Aegean Sea, particularly around the Greek islands and their EEZs. Ankara argues that Greece unlawfully extended its maritime boundaries and airspace control while militarising Aegean islands that are supposed to remain demilitarised.

Turkey also increases its regional presence militarily. In northern Syria and Iraq, it fights Kurdish forces and expands its sphere of influence. Turkey controls several areas in Syria and operates military bases in Iraq for PKK operations, asserting influence over Mosul and surrounding areas. Ankara supports Azerbaijan’s efforts to reclaim Karabakh – a goal that was “de facto achieved in 2023,” according to the expert. Turkey provides Baku with diplomatic and, at times, military support against Yerevan.

Even without formal territorial claims, Turkey continues to expand its geopolitical reach. The “Blue Homeland” (Mavi Vatan) doctrine envisions Turkish control over the Black Sea, the Aegean, and the Eastern Mediterranean, particularly in terms of energy resources. Ankara pursues this through military-industrial development and naval expansion. It aims to fill the gap left by waning American influence in the Middle East, especially in Syria, Iraq, and the Gulf. It is strengthening its regional military presence and building economic ties with Iran, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and others.

Turkey is also expanding into Africa, operating military bases and training centres in Somalia and Libya, and forging ties with other African nations.

Turkey’s global and regional policies are built on imperial traditions, perceived or real geopolitical challenges, and national identity. Ankara’s active and expansive foreign policy uses a mix of military, economic, and diplomatic tools to grow its influence in the Middle East, Mediterranean, Balkans, and Africa. “Both the neo-Ottoman strategy and the ‘Blue Homeland’ doctrine show that Turkey is striving to become a regional hegemon in the 21st century,” concludes Egeresi.

Top 3 Books to Understand Ankara!

Turkey and the West: Fault Lines in a Troubled Alliance

Author: Kemal Kirişci

Publisher: Brookings Institution Press, 2018

Kemal Kirişci’s book provides a thorough analysis of the relationship between Turkey and the West, with particular attention to recent political tensions. The author points out that Ankara’s authoritarian trajectory and ambitious foreign policy are causing it to drift further from its Western allies, while simultaneously forcing a reassessment of its geopolitical position. The book emphasises the importance of pragmatic cooperation, especially in light of relations with Russia, the Syrian conflict, and the Kurdish issue.

Turkey’s Pivot to Eurasia: Geopolitics and Foreign Policy in a Changing World Order

Editors: Emre Erşen & Seçkin Köstem

Publisher: Routledge, 2019

The volume Turkey’s Pivot to Eurasia analyses Turkey’s foreign policy shift, during which it is not only distancing itself from the West but also forging increasingly closer ties with Russia, China, Iran, and India. The authors examine to what extent this geopolitical opening reflects a strategic realignment, as well as the challenges and opportunities it presents for Ankara. The book offers a detailed and balanced view of Turkey’s search for a new international role amid a transforming global order.

Turkey under Erdoğan: How a Country Turned from Democracy and the West

Author: Dimitar Bechev

Publisher: Yale University Press, 2022

Dimitar Bechev’s book provides a comprehensive analysis of Erdoğan’s two decades in power, during which Turkey gradually shifted from reformist promises toward an increasingly authoritarian direction. The volume explores how Erdoğan managed to remain in power within a formally democratic system and offers a detailed account of the domestic and geopolitical factors that made this possible. Bechev places special emphasis on the shift in foreign policy, the role of the “neo-Ottoman” strategy, and the intertwining of religion, nationalism, and political power in Turkey.