How a small Czech porcelain company became Michelin’s key partner

author: Sámuel Kálló

From London to Singapore, the doors of the world’s most exclusive restaurants bear the same unmistakable symbol: a glossy red Michelin plaque adorned with stars. But where do these iconic signs actually come from? The manufactory that produces them operates in Brno, a Czech city not previously known as a powerhouse of global gastronomy.

Smalt Brno is a small workshop based in Brno that produces several thousand Michelin plaques each year. Bound by strict contractual obligations, the company cannot disclose exact figures, but its director, Josef Fišera, reveals that production grows year on year—and that the much-coveted star plaques are usually completed early in the calendar year.

Founded in 1993, Smalt Brno specialises in enamelled porcelain plaques. But how did a Czech manufacturing workshop become a supplier of one of the world’s most prestigious gastronomic symbols? According to Fišera, the journey took several years. The first—and by far the greatest—challenge was achieving the perfect red. Months of testing followed. Michelin guards its brand identity with almost religious fervour, and the colour red is precisely defined; it was up to Smalt Brno to find the exact pigment combination to match it.

The task became even more complex when EU regulations rendered the original pigments unavailable, forcing Smalt Brno to develop an alternative solution. The obstacle was successfully overcome, and today the red Michelin plaques travel from the Czech Republic to restaurants all over the world.

These days, Michelin plaques are far more than simple objects. They are delivered in presentation boxes, complete with bespoke fixings and carefully considered accessories. The company even supplies detailed installation instructions—for example, warning recipients not to hammer the plaque onto the wall, as this could damage such a refined product.

Of course, Smalt Brno does not work exclusively with Michelin. Its annual output amounts to around 300,000 enamelled porcelain plaques and signs for clients including Bosch, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Carlsberg and TotalEnergies. Even so, Michelin remains one of its most important partners.

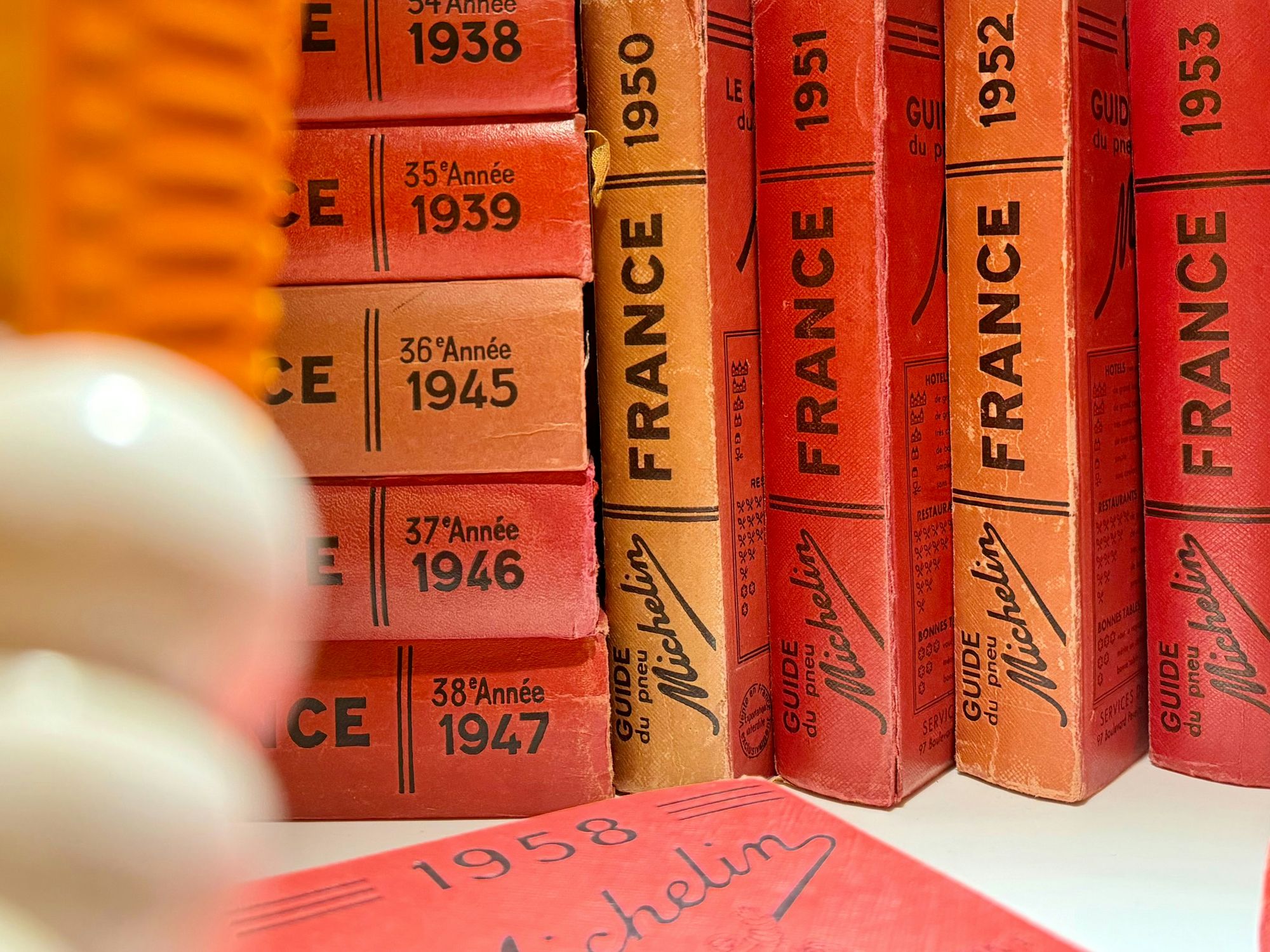

The original Michelin story is just as fascinating, if more widely known. Michelin stars were not born out of a gastronomic obsession, but as a marketing idea devised by a tyre company. In 1900, the automobile was still a futuristic novelty in France, with only a few thousand cars on the road. Two French brothers, André Michelin and Édouard Michelin, commissioned a small guidebook to promote their tyre business. It contained practical information on hotels and restaurants, along with routes and travel tips. The logic was simple: if more people drove and travelled further, tyres would wear out faster—and more Michelin tyres would be sold.

The guide was initially distributed free of charge to motorists. The real turning point came in 1920, when Michelin realised that people value what they pay for. The guide was priced at seven francs—and sales soared.

True innovation followed in 1926 with the introduction of the star system. One star signified “A very good restaurant in its category—worth a stop”; two stars meant “Excellent cooking—worth a detour”; and three stars denoted “Exceptional cuisine—worth a special journey.” The system proved so effective that it now shapes not only Michelin itself, but the entire world of fine dining.

Michelin continues to cultivate its aura of mystery: inspectors remain anonymous, evaluations are conducted in strict secrecy, and the sole criterion is the quality of the dining experience.

Brno and Central Europe

Within the region, Hungary currently boasts ten Michelin-starred restaurants: two with two stars and eight with one. The elite includes Platán in Tata and Stand Restaurant, both holding two stars. One-starred establishments include Babel, Borkonyha, Costes, Salt, Rumour, Essência, 42 Restaurant, and Pajta in Őrség.

In Czech Republic, the first nationwide Michelin Guide was published in 2025, having previously focused solely on Prague. A major milestone followed when Papilio, led by chef Jana Knedly, became the country’s first two-star restaurant. Located in Vysoký Újezd near Brno, in the former stables of a château, Papilio offers six-, eight- or ten-course tasting menus inspired by Knedly’s childhood memories and rooted firmly in local ingredients. The country’s eight one-star restaurants include Field, La Degustation Bohême Bourgeoise, Casa de Carli, Levitate, Štangl, Entrée, Essens, and La Villa.

Poland has also gained momentum in recent years, with six Michelin-starred restaurants. Kraków’s Bottiglieria 1881 holds two stars, while Arco by Paco Pérez earned Gdańsk’s first star. The full list also includes Giewont, Rozbrat 20, NUTA, and Muga.

Slovakia does not yet have a Michelin-starred restaurant, but regional trends suggest this may only be a matter of time. In 2025, Gault&Millau published its first Slovak guide. While often described as Michelin’s “sibling”, it operates under a different system. ECK in Bratislava received four chef’s hats—an indicator of very high quality, though not a Michelin star. For now, Slovakia remains in waiting, while Hungary and the Czech Republic lead neck and neck, with Poland close behind.

Michelin stars matter. When Platán earned its second star, it sent a clear message that Central European gastronomy belongs on the world stage. And when the plaques for the world’s best restaurants are made in Brno, it signals something equally significant: the region is now fully integrated into the global culinary landscape—and has become a player of real importance.