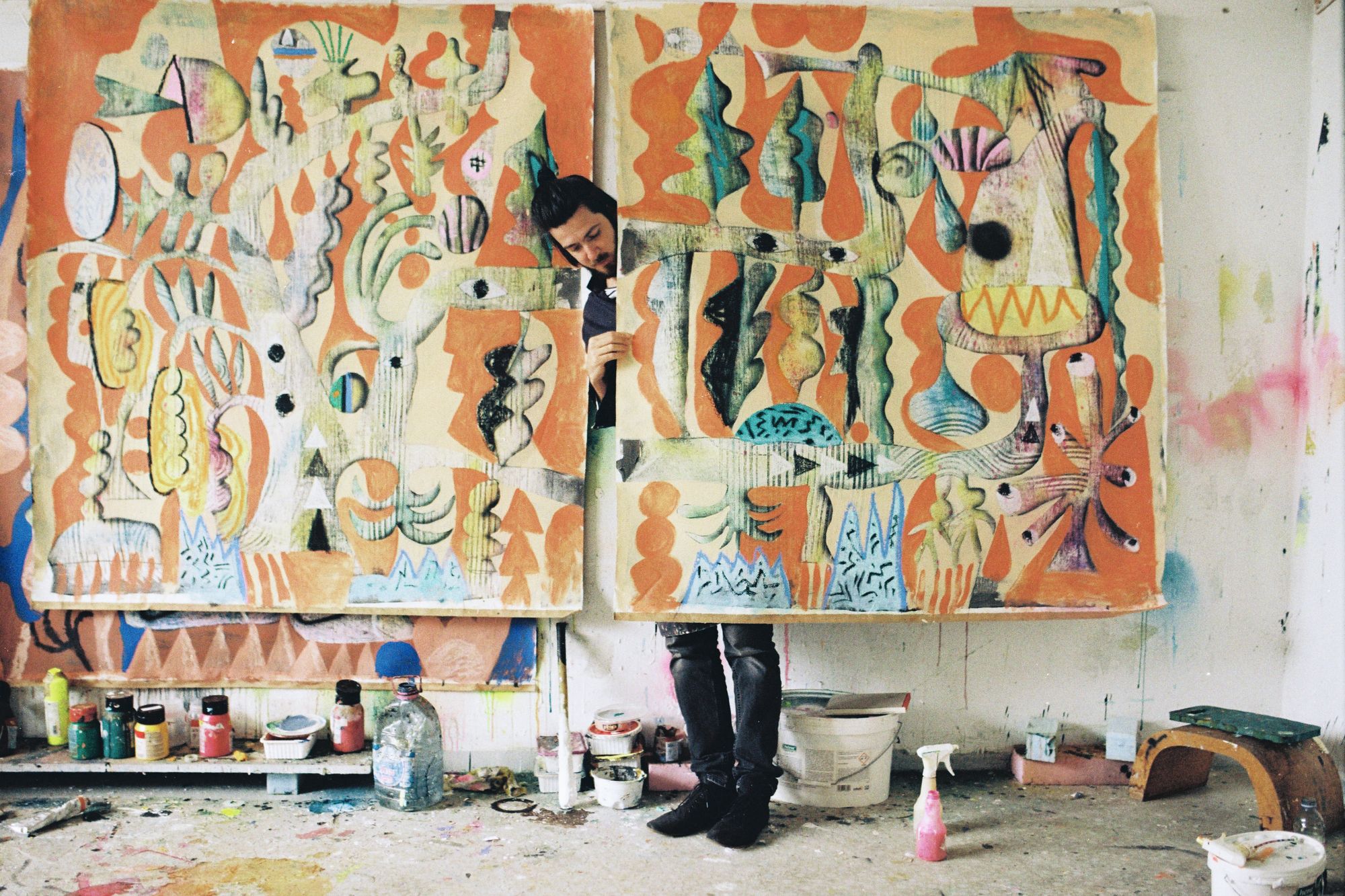

It’s not my first time in the studio of Józsi – we’ve known each other for a long time, and we’re almost as close as friends are – but it’s always a little different. The colors and dynamics of the works in progress and those waiting to be shipped off always give the space a new and exciting atmosphere. He has been building his career very steadily, mostly beyond the border, rather than in Hungary-Antwerp, Berlin, Hong Kong, and Vienna; one followed the other in recent years. His mature, yet organic, naive work is just fun to look at and to be in the same room with – I tried to spend a bit more time with him this time so that I could scrape a few layers off him, much like he does with his favorite technique.

I was going to save it for the end, but it might be easier if I just start with what I'm most interested in with you. If you could take capitalism out of the equation of artistic practice, would you do it?

(I hereby introduce to him my position in a monologue; an artist’s territory is his studio, his brain, his canvas, his hands, and what he wants to say about the world through this medium – and what someone does with that message later is a whole other act, but we have to accept that capitalism is also part of the game.)

Well, I have to confess that for most of my life, I didn’t really think about this – or rather, I simply ignored it. I think a fundamental reason for this is my attitude towards money, which is the same: almost non-existent. It has to be done. You have to be “born into” the act of what you’re doing, and if you do it, something happens. Of course, it’s not easy when you’re aiming for eternity, but I find that it’s the best way to get the dynamics in order. But I think the part of the equation you mention is the gallery’s domain in the classic setup. They are in effect sellers. I make the liquor, they put it on the shelf, and the profits come with it.

All this brings me back to the question of youth – you were once a young and burgeoning spirit –, do you think that you have a common language today with this new, perhaps a bit more business-oriented generation? Do you observe them, look for something in them?

I'm following a bit of a “like-dislike principle” here, which creates a sort of charming, unprofessional selection of who I listen to and who I see something in. In a way, I have to genuinely like what I see, but I don’t necessarily have to agree with it – it can still get me hooked.

Honestly, how does observing other artists and their work affect you (i.e. painters in a narrower sense)? Whether consciously or unconsciously, have you ever discovered such an “impression” on your own canvas?

Naturally, I will consider something good that I could accept as my own in a way, at least its elements, or whose gestures and motivations I understand and know.

In the meantime, of course, I may discover an opportunity, but for me, it’s all gone in that moment; if I observe a scene in someone else’s work that “I could have done myself”, there goes the magic. Nevertheless, I can’t exclude myself from the process, so if I look at something, it’s my brain that makes something else out of what I see, the cradle of an “imported element” doesn't matter – it’s still very much me. But I have a fairly strong filter.

CHANGE OF PERSPECTIVE

An often mentioned, important element of your work is repainting. Building on the previous question, do you believe that this method might subconsciously resonate with this?

If I become aware of this, it also spoils my attitude toward myself or the painting, so unfortunately yes, this aspect can be of some importance – but not only when I paint over something, but even when the motif is conceived. I divide these into sets; the annoying one includes these images, drawings, and elements. But they can end up in this set for many reasons: they annoy me because they don’t work out, or because I thought during the drawing process that they would make a good painting, but they don’t. This is a realm of painting that we know little about.

(Meanwhile, notebooks full of drawings appear, all with cheerful covers. He used to work in only one at a time, but now he always carries one with him, so there are several in use in parallel.)

...so then I pick up an older work from the ‘annoying set’ later and realize that I’ve been working with those motifs for two years, it just seemed like a premature idea at the time.

Interesting. What do you think about rotating the artwork? What does such an act evoke in you?

When they are turned over?

No, rotated vertically. Although that would be an interesting topic, as well.

I wouldn’t like my picture on a wall like that. Many say “Oh, it would work this way, or what way too,” which implies to me that they haven’t really connected with the artwork for some reason. I try to emphasize that, although the works are figurative, I don’t want to tell the audience what they see, I leave it up to them – but I don’t mean that I’m looking for hints for another perspective.

That’s perfectly valid – but perhaps for some taking in, experiencing the work might be too cathartic, it’s enough for them to know whose picture they are looking at.

That’s quite possible.

By the way, can you paint with your left and right hand, as well?

Well, actually, no.

(And then he pulls out the famous, Csató-style dark blue painter’s cloak, along with a stretching frame, some paint, and brushes.)

CANVAS, FRAME, PAINTER’S CLOAK – leaving a trace

(As he starts to apply the canvas on the stretching frame, he tells me that he has been getting the frames from a nice couple in Transylvania for years.)

Even though I’ve been following your work for a long time, I didn’t know that you always paint on the wall. Why is that?

I really like how it allows me to scratch a deeper layer of the surface, as the wall supports the image. If I worked on the frame, I would punch holes in the canvas – but this way I can save the frottage of each wall for that particular painting. When this piece leaves for Hong Kong or Sicily tomorrow, it will have the imprint of my Budapest studio wall. It is actually a metaphor for creation and travel for me, an intimate act.

I just noticed another interesting motif in your work: the figures in your paintings – at least the ones that are here now – that are close to the edge of the canvas actually run off it. Is there a reason for this?

I don’t like the meaning to stop at the edge of the canvas. I treat the paintings as objects, and this move, beyond practical reasons – there is more space to stretch when I consider the margin – can be a bit of an extension of the pattern, a reinterpretation from another point of view, which I find exciting.

How much do you like these essential physical elements of the work? How much is stretching part of your creative sessions here?

A hundred percent, it balances me out. If I come in and I don’t feel like painting, I can still stretch, and that’s a completely different brainwork.

You’re preparing for a solo show at the renowned Haverkampf Leistenschneider Gallery in Berlin. What is different about preparing for such a project? How do you experience the openings?

I’m not too much into openings. When I was there, an artist told me how much he loves openings, because that’s when he feels that the work is done and is followed by this well-deserved part. But for me, it’s not very comfortable, although I’ve definitely gotten used to it over the years. The focused, ‘internal’ work in the studio is closer to me than these events. However, I don’t want to hide either, it’s nice to meet people, but given the choice between the studio and this, it’s certainly the former.

THE VIEWER’S EXPERIENCE

While we are involved in a rather intimate and special moment – Józsi finishing a colorful patch on a picture in front of our eyes –, I ask him how interested he is in his audience’s experience of seeing one of his paintings.

He replies not really, the fact that a picture reminds someone of their grandmother’s vase is not really relevant, and he doesn’t think it should be.

I press him a little more and inquire whether a sincere, deep experience would affect him; if I told him, say, that I was struck by the eyes in two of his pictures here – while one gives me a reassuring, direct, yet curious impression, the other makes me feel a bit caught off guard, tense.

It’s the same feedback category for me as the grandmother’s vase. Both in the physical and metaphorical sense, it’s a completely different story and layer for you than it is for me. At times it’s so absurd – since you brought up the eyes – I can't even remember exactly how they were formed, because they started out as seeds – or at least that was my intention, as spots. That’s why I don’t like to impose a narrative on anyone about the images because we don’t have the same starting point.

Fair enough. Nevertheless, are there any professionals you respect, whose words are of relevance?

Of course: my master Dóra Maurer, for one, but there are others as well. I was lucky at school, teachers liked me, and even if they didn’t always understand me, they let me work, which is crucial. Dóra didn’t necessarily agree that this kid was painting cacti, but she couldn’t help it, and that allows me to paint today without expectations or fear. I can’t work in a state of anxiety or agitation, I’m unable to create anything exciting in that mood.

Meanwhile, the last patch of paint is done, and looking at the canvas, it feels crazy good to see it come to fruition.

THE LYRICAL SELF

How do you switch off, recharge, and come back here with a fresh spirit?

I’m reading, several books in parallel, alternating right now, for example, between Walden by Henry David Thoreau and A Philosophy of Walking by Frederic Gros. I really like this kind of sincere, respectful approach to nature, and the way they describe it is quite similar to how I experience it.

In this respect, it’s quite clear that after spending some time outdoors, a kind of trance state is induced, so that even a motif that I’d previously put in the annoying category can appeal to me – this is what happened recently with a work done for the Erika Deák Gallery. I made a painting – figures with umbrellas–, but I didn’t like it. Then, as I put it on the wall, I thought about what this composition would look like with the people hiding under a table –this is what brought to life the piece that was hung over a table opposite the exhibition entrance. Even though I don’t like to be that narrative, because it’s usually a single-channel thing, this was a very good moment and it worked well on the canvas.

For me, it’s important to have these associative, linear steps, along with the repainting and the light, fluid processes – that’s how I work.

It’s as if there was a constant state of search surrounding you – you don’t stick to a particular visual style for too long, but you don’t leave your signature, well-defined terrain.

Yes, perhaps. It comes from my nature, but it’s not very conscious. I don’t know if I could find a routine that would interest me on the same level over a longer period.

Painting is something like that, strictly speaking – and you’ve been doing it for decades.

Of course! I tend to think about where I am in terms of skill level, regardless of what phase I'm in – whether I could, say, create a painting in a completely different style tomorrow. It also occurs to me from time to time when I’m flipping through notebooks, wondering if I could create certain technical elements and if so, how.

That’s exciting to hear, it has a bit of a behind-the-scenes feel to it. Would they remain strictly on the experimental table?

Not necessarily. What I've found with drawing and painting is that with experience comes knowledge – it may sound simple, but I haven't acquired any real new knowledge or practiced intensely, I've just deepened my insight, my knowledge of things, of the world, perhaps I understand it better, so I can adapt its layers more easily, which when I was younger was strictly visual – and that’s an enormous relief.

Photographer: Dániel Gaál | @daniilgal