Vlasta Kubušová is rethinking what plastics are for — and how long they should last. As co-founder of Crafting Plastics! Studio, she works with biopolymers designed to transform, decompose, and respond to their environment. In this interview, she talks about materials as living systems, Central Europe’s hands-on design mentality, and why sustainability is a direction, not a finish line.

How did your connection to material research and sustainable design begin? What were the key experiences that led to founding Crafting Plastics! Studio?

It started quite organically. During our studies with Miro (my partner and co-founder of CP!S), we became fascinated by the invisible side of materials – how they are made, what they’re made from, and how they behave once we’re done with them. I realized that design decisions extend far beyond the object itself; they affect ecosystems, energy use, and people’s habits. Over time, we became less interested in designing final products and more in understanding the material processes behind them. This was partly because we could not find a reliable alternative to the fossil-based plastic for our projects. This curiosity eventually led to further studies at UDK in Berlin and later to the start of Crafting Plastics! Studio. Together with my co-founder Miro, we wanted to create a practice that connects science, design, and sustainability on an equal level. What began as small experiments with biopolymers slowly evolved into a long-term collaboration with researchers and manufacturers, and a shared vision to build materials that belong to natural cycles rather than stand outside them.

Your studio is well-known for experimenting with bioplastics. What are the biggest challenges and opportunities you see in working with these materials?

The challenges are very technical but also cultural. Bioplastics behave differently from what industry is used to, which means processes and expectations have to change too. That takes time and trust. But the opportunity is creative. These materials invite you to design for transformation instead of permanence. They can be programmed for a specific lifespan – they age, react, or decompose – and that makes them deeply expressive. Natural materials are not static, and now we can design them to match the required durability. Consumers and manufacturers, however, need to get used to materials that do not outlive them the way petroleum-based plastics do.

Do you believe biopolymers could ever replace conventional plastics on an industrial scale?

Not in the same way, and not within the same system. Biopolymers shouldn’t simply copy what fossil-based plastics do; they should lead us toward a completely different way of thinking about production. Plastics exist in hundreds of variations, and NUATAN®, our material based on PHAs, has shown that biopolymers can perform on a high level while remaining compostable. We’ve applied it across various industries, from fashion to automotive collaborations. To replace most fossil-based plastics, there won’t be a single solution. We need a diverse set of regenerative alternatives that are, ideally, sourced and produced locally. Even if the science works and we have several good materials, the real challenge remains: building a system around them that is truly regenerative.

The word “sustainability” has become almost ubiquitous. How do you define it in the context of your work?

For me, sustainability is not a goal but a direction. It’s a process of constant calibration – understanding limits, listening, and adjusting. It’s about creating balance rather than perfection. In our studio, that means looking at a material’s whole life and thinking about the relationships it forms along the way: with people, with tools, with natural resources. True sustainability feels like empathy in action.

Sustainable design is often seen as involving aesthetic compromises. How do you balance responsibility with beauty?

I think responsibility can actually deepen beauty. When you work with respect for materials, that care becomes visible. Our bioplastics have their own tactility and warmth; they’re slightly irregular, and that imperfection feels real. In the Sensbiom project, we use environmentally-active biomaterials that respond to sunlight or temperature, creating subtle colour shifts. Those reactions make the object part of its surroundings. For me, that’s where beauty lives — in the dynamic connection between material, environment and us.

In your opinion, how does Central European design thinking differ from Western European approaches?

In my eyes, Central Europe has always been shaped by improvisation. We’ve learned to do a lot with very little. That history taught us flexibility and persistence. It also gave us a closeness to materials and to making things by hand. While Western Europe often has more infrastructure and institutional support, designers in this region have developed a kind of pragmatic imagination – we combine experimentation with practicality. That balance feels very contemporary.

How does the region’s historical and economic background influence the potential for sustainable innovation?

It gives us both limitations and freedom. After the political transitions, many large industrial systems disappeared, but that allowed smaller, more agile ones to emerge. Today, independent studios and labs can move quickly, test prototypes, and collaborate with local producers without heavy hierarchies, even though there’s a perception that few manufacturers remain in Slovakia. In the Czech Republic, for instance, the situation is quite different – local designers really thrive there thanks to close collaboration with local product producers and manufacturers. There’s also a growing awareness of regional resources, from agricultural byproducts to forest materials. These can become the foundation for local circular economies. The complexity of our region is not a weakness; it’s a condition for invention, though it still needs much stronger support in the early stages of research.

What does the development of a new material or product look like in your studio?

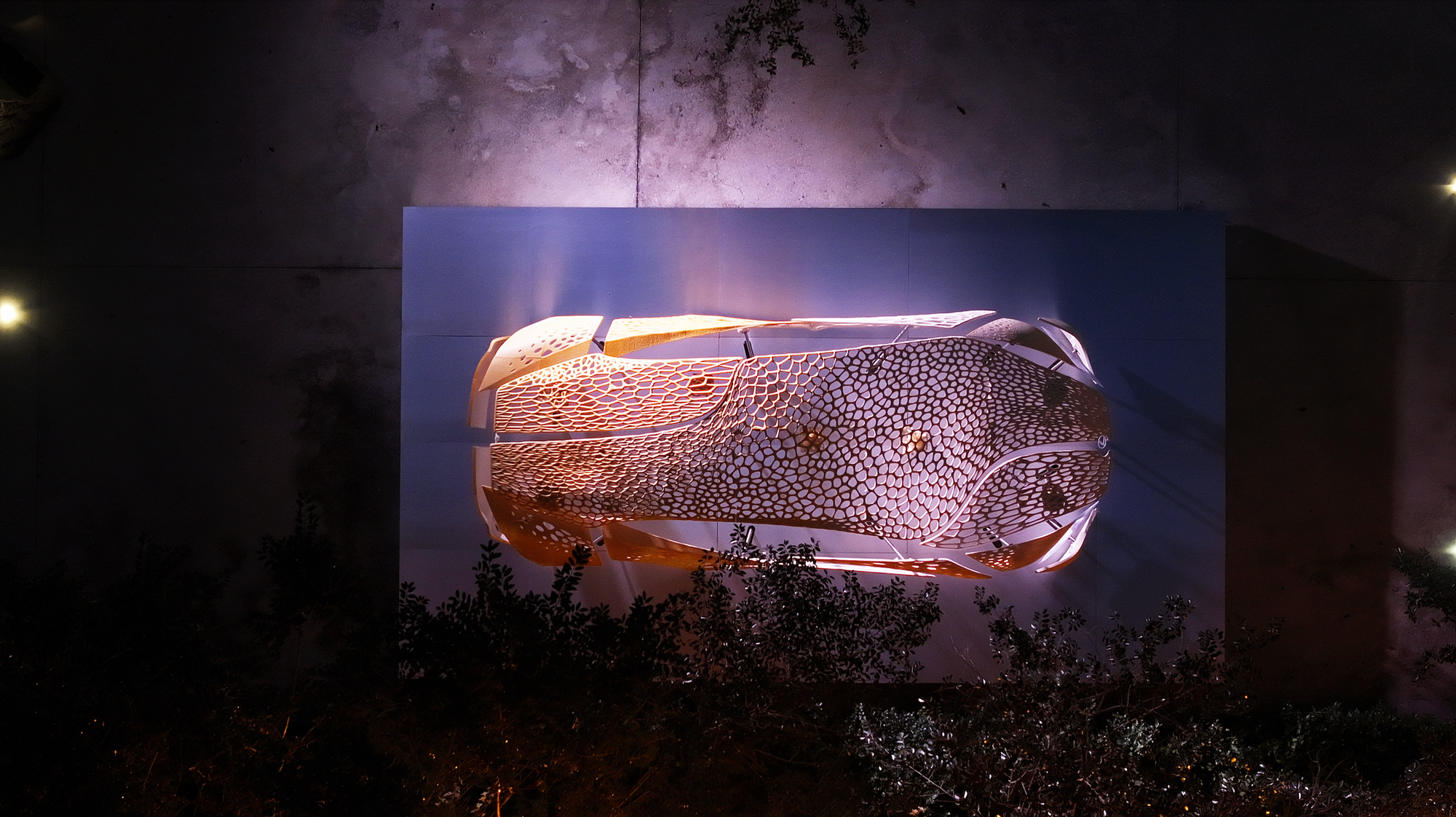

The interesting thing about our studio is that it operates between a design and research studio and a material development platform. This allows us to test our material ideas directly on our own products. Each stage of material development or process optimization is proven through application on a new technology. For example, when we developed a filament for 3D printing, we demonstrated how it could be used to design and produce interior products that are both durable and water-resistant. Later, when we achieved higher temperature resistance, it enabled us to create collections such as a gastro system for festivals and city markets. Most of our product collections are made with NUATAN® – a series of biopolymer blends developed for value-added applications, with the goal of integrating them into the consumer system on a meaningful scale, where people can truly start using and experiencing them. We work closely with scientists and engineers, but intuition plays a big role too. Sometimes an unexpected colour shift or texture leads to a new idea. We try to document everything, because every mistake teaches us something about the material’s nature. It’s a dialogue more than a process. Another part of our research is more experimental and focuses on materials that are dynamic rather than static. We explore compounds that can act as sensors — reacting, for instance, to UV levels with colour change, or potentially detecting toxins to help us navigate the often invisible but crucial environmental shifts around us. This path often culminates in large-scale installations, such as Sensbiom or Liminal Cycles for Lexus in Design Miami.

How crucial is interdisciplinarity in your work — the collaboration between scientists, engineers, and designers?

It’s absolutely essential. Developing sustainable materials is too complex for any single discipline. Usually, scientists bring knowledge of composition and behavior, engineers translate that into scalable processes, and designers connect it all to people through form, experience, and meaning. In our case, we try to combine all these skills through transdisciplinary collaboration from the very beginning of the material or project development process. This approach helps us understand not only the technical aspects of development but also the broader meaning of the work within a much more complex system. At our studio, collaboration is not a linear process but an ongoing exchange. We work closely with architects, researchers of various fields, chemists, and engineers to test new material blends and adjust processing techniques, while they join us in exploring how those materials look, feel, and perform in real contexts. Many of our ideas emerge from these intersections. For example, the research behind Sensbiom began during my Fulbright exchange as an exploration with bioengineers on how to create materials capable of sensing toxins in the environment through the latest methods in synthetic biology. Later, this work led us to investigate chemical interactions and solar-active biomaterials, as we wanted to translate this research on interactive bioplastics into practice and show people the potential of dynamic, living materials. We keep our collaborations open and horizontal. Everyone learns from everyone, and that shared curiosity often leads to unexpected discoveries. Interdisciplinarity is not only how we work — it’s the mindset that keeps our practice alive.

What’s the next big challenge or goal for Crafting Plastics! Studio?

Right now, we’re focusing on bringing our materials into broader production to make our research truly matter in terms of real usability. I would like to see these innovations in everyday use, integrated into real products and environments. Without incorporating solutions like this into practice, material development remains only a nice experiment or a promising prototype. NUATAN® is now ready for larger applications in terms of scale , and we’ve already started pilot projects with several clients, which is very exciting. At the same time, education has become a major part of what we do. Through our Better Matter studio at Design Academy Eindhoven, we encourage young designers to work across disciplines and to think of materials as systems, not isolated objects. Our long-term goal is to nurture a material culture that is both advanced and sensitive – one that understands that innovation and care can grow from the same place.