The Hungarian pavilion of the recently closed Expo 2025 attracted more than a million visitors, let's see what the magic was: we spoke with the pavilion's creator in the spring print issue of Hype&Hyper.

On April 13, 2025, the eyes of the world turned to Japan, where the Osaka World Expo officially opened its gates — and Hungary took part with a pavilion of its own. While the exhibition has since closed, the creative processes, decisions, and cultural stakes behind Hungary’s participation continue to raise fascinating questions. We spoke to the team behind the Hungarian Pavilion about how they aligned visual identity with cultural messaging for an East Asian audience, and how they managed to stand out in the vibrant whirlwind of a global exposition.

The idea of the world expo dates back to a time when most people couldn’t travel, and these itinerant exhibitions offered a way to discover the world. Countries could present their latest scientific and technological innovations, and their pavilions were often designed by the most prominent artists and architects of the time. Since the first expo in London in 1851, the purpose of these events has evolved, but the mission remains largely the same: to strengthen national image, build international economic ties, and promote tourism. At the 2025 Osaka Expo, countries expected their participation to drive interest among East Asian travelers and boost global appeal. In terms of its economic and cultural impact, the expo ranks just behind the World Cup and the Olympics.

This year’s theme — Designing Future Society for Our Lives — reflects the need for sustainability and innovation. Since the beginning, host countries have marked the expo with monumental, iconic structures — think London’s Crystal Palace, the Eiffel Tower in Paris, Seattle’s Space Needle, or Brussels’ Atomium. For Osaka, Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto was commissioned to design the overall site; known in Hungary for the House of Music in Budapest, Fujimoto created the central structure of the expo: The Grand Ring. Spanning 60,000 square meters, it stands on the artificial island of Yumeshima in Osaka Bay and symbolizes unity among the participating nations. The two-kilometer perimeter ring of wood represents a contemporary interpretation of traditional Japanese timberwork — a fitting metaphor for Japan as a country rooted in tradition yet driven by cutting-edge technology.

People Behind the Pavilion

The creative team behind the Hungarian Pavilion faced the challenge of designing something that not only captured the essence of Hungarian identity but also resonated with an East Asian audience — and did so on a scale grand enough to catch the attention of thousands of visitors passing through the bustling expo grounds.

The pavilion’s creative concept was developed by Drozsnyik Dávid and Ördögh László, with architectural design led by renowned Hungarian architect Gábor Zoboki. The artistic direction was conceived by Bence Vági, award-winning director and choreographer, while Balázs Csapody oversaw the culinary vision. Boglárka Bódis designed the uniforms, and István Szalonna Pál curated the cultural programme. “We wanted to inspire a desire in visitors to travel to Hungary,” said Ördögh. “We approached the concept as an experience design project, beginning with parallels between Hungarian and Japanese culture. What we found in common was a deep respect for multigenerational traditions and a shared appreciation for nature-centric ways of living. The idea is that to move forward in the present and into the future, we need to understand the past.” As Drozsnyik added, “Music became a universal language between these two geographically and culturally distant nations — an authentic, emotional core within the visitor experience.”

The Peaceful Face of the Hungarian Countryside

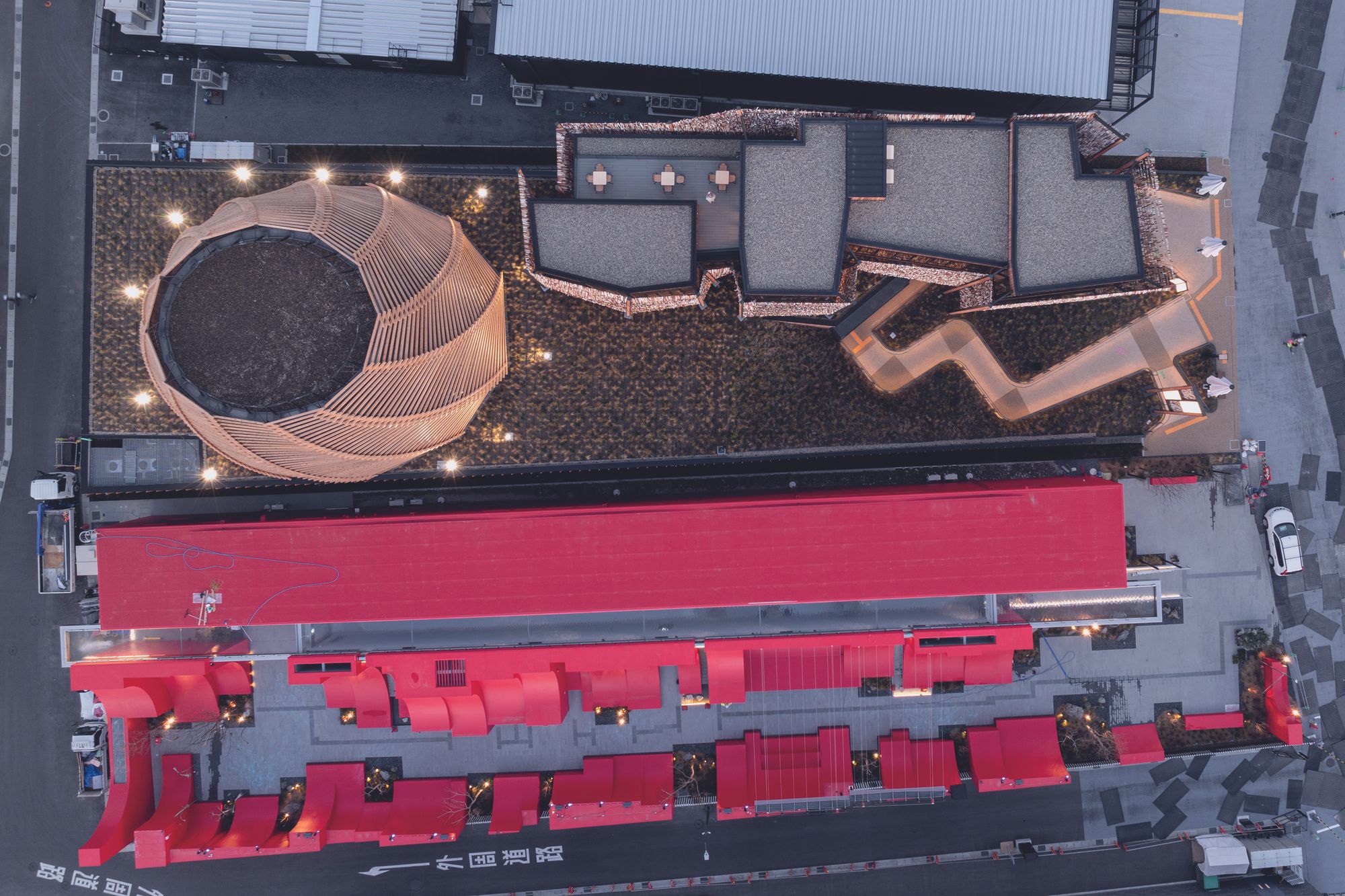

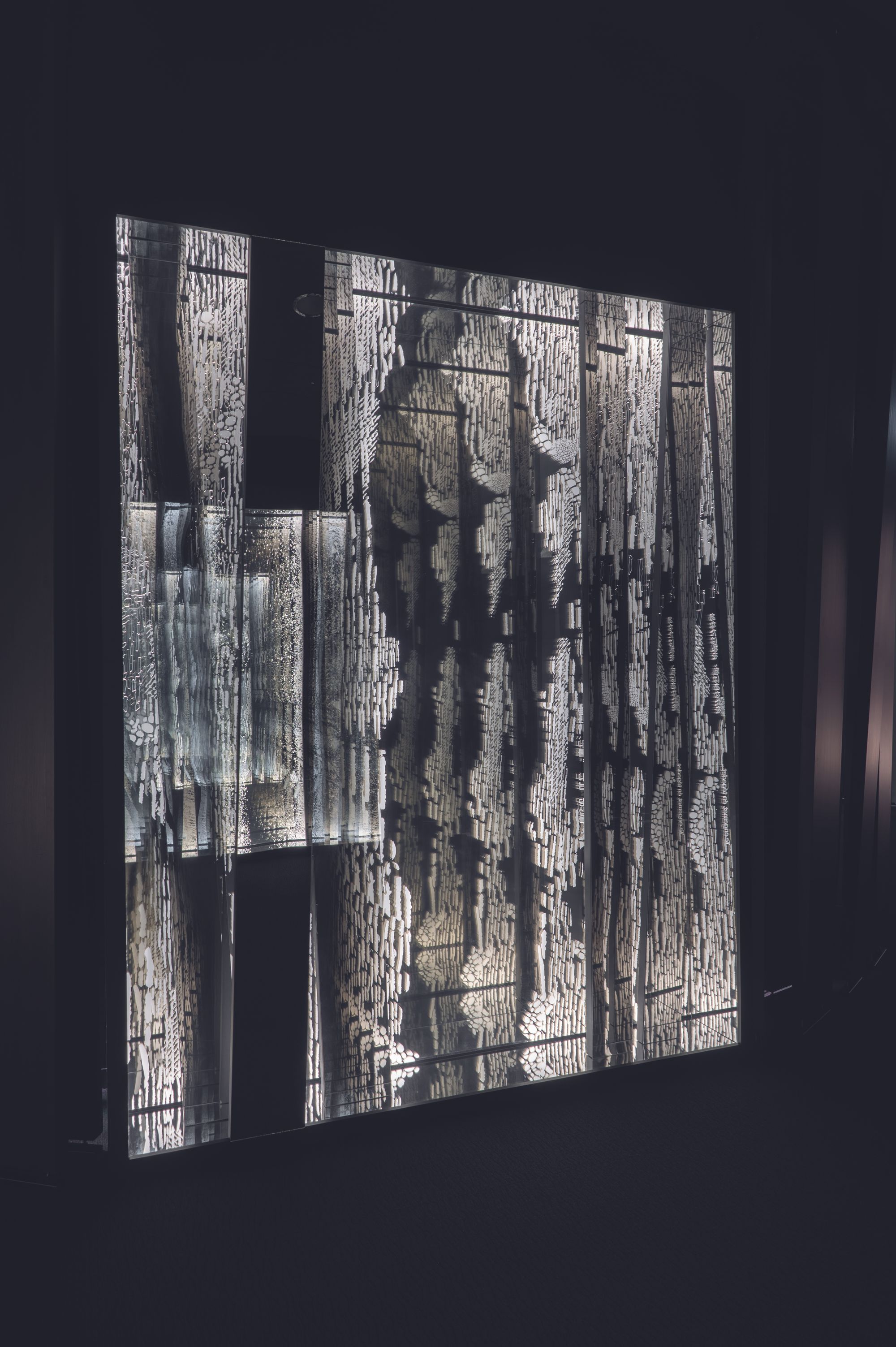

“We built the architectural concept around three natural landscapes — the forest, the meadow, and cultivated land — each of which holds deep significance for both Hungarian and Japanese people,” says András Csiszér, Design Director at Zoboki Architects. “We translated these landscape types into architectural language and merged them into a single, cohesive whole. At the heart of the pavilion lies the Zengő Dome, an immersive performance space that reimagines the haystack — a symbol of cultivated land — as an abstract, contemporary form. Our goal was to stand out at the expo not through noise, but through the power of quiet.”

“Our plot, like those of the other national pavilions, followed Sou Fujimoto’s masterplan: long and narrow in shape,” Csiszér continues. “As we explored the spatial possibilities, we noticed a striking similarity between this format and the traditional ‘comb-like’ layout found in many Hungarian villages, where long, narrow plots stretch out behind single-street houses — a pattern also present in Japanese rural settlements. Instead of filling the plot to its limits with a single large building, we let the pavilion breathe. We left open space, creating a sense of rhythm and air.”

Grass, Wood, Bloom

The architects collaborated with 4D Landscape Architects to bring the meadow concept to life — a task more complex than it might seem. The vegetation had to reflect the characteristic flora of Hungarian fields, withstand the heavy foot traffic of a world expo, and most importantly, adapt to the local climate. Since no plants could be imported from Hungary, every species had to be sourced in Japan.

From the moment visitors stepped onto the plot, their journey was carefully choreographed. They walked through the meadow, entered beneath the canopy of the forest — or rather, the building that symbolizes it — and arrived at the Zengő Dome. Along the gently sloping path leading to the dome, the first segment housed practical functions such as information desks and restrooms. Then came a transitional space: a narrow woodland walkway designed for deceleration. Here, visitors could shift gears and tune into a different rhythm before entering the infinite darkness of the dome’s interior, where the immersive experience would begin. On the way out, visitors passed through a small exhibition showcasing the visual richness of the Hungarian landscape. From there, they either rejoined the buzz of the expo via the gift shop or extended their experience by exploring the upper levels of the forest-inspired structure.

The first floor housed a restaurant — accessible independently from outside as well — while the second served as a venue for community events and business meetings. The canopy-inspired exterior design of these upper levels responded to the natural forces at play on Osaka’s seaside. Steel cables were strung between hybrid steel-and-wood columns, holding up textile panels in varying shades. These fabric “leaves” mimicked the shimmering of real foliage, animated constantly by the ocean breeze. Besides creating movement and atmosphere, they also served a practical purpose: shading the structure and reducing energy consumption.

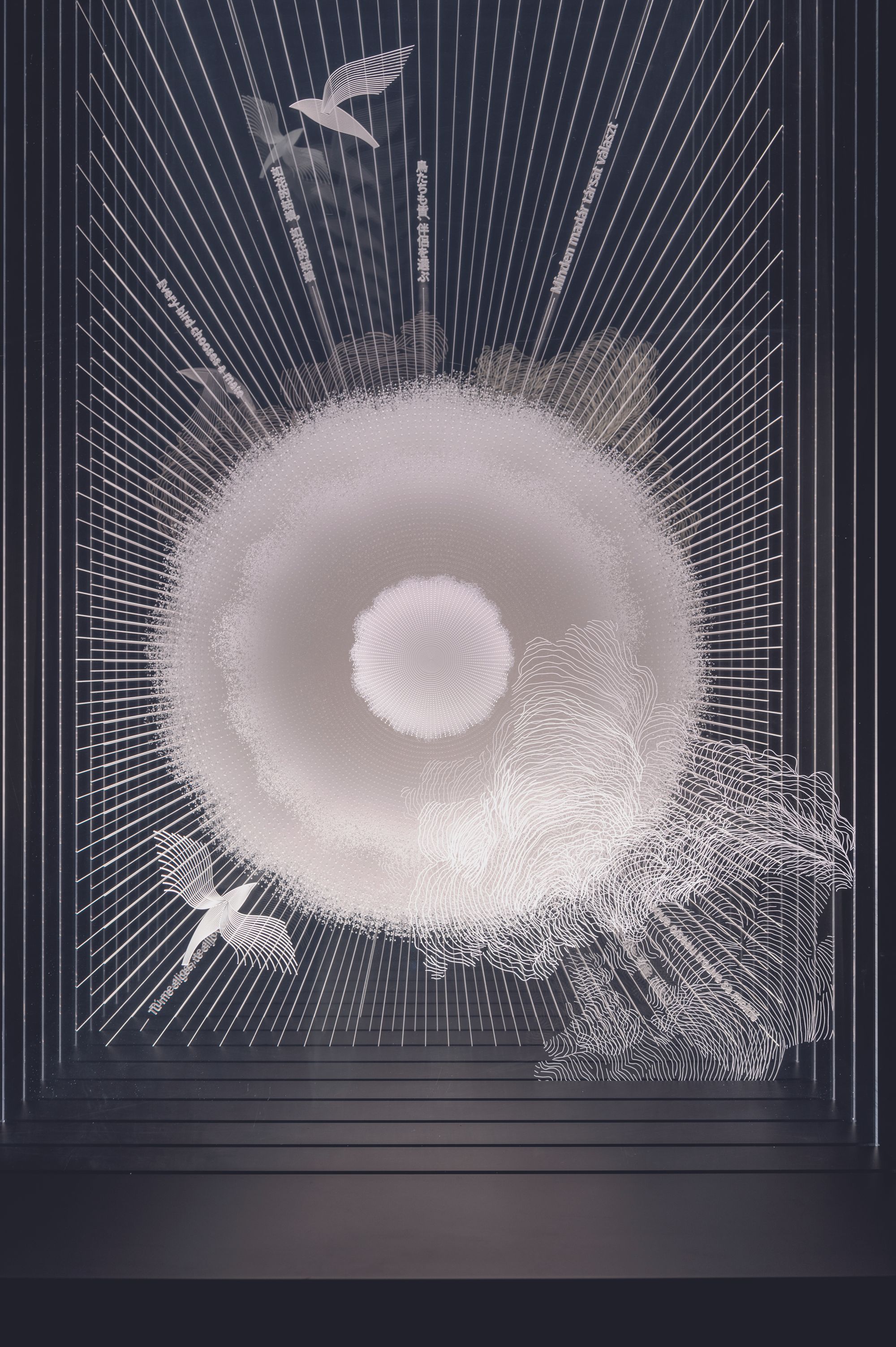

The Zengő Dome itself was clad in timber — a freestanding, gently twisting shell that surrounded the structure without touching it. The design drew inspiration from traditional Japanese architecture and the timberwork used in the Grand Ring, fusing local influences into the Hungarian concept. Beneath the wooden shell, the dome was enveloped in two membrane layers. The outer layer ensured acoustic and light insulation, allowing the space inside to become fully immersive. The inner membrane served a more symbolic role: designed to evoke a night sky filled with countless stars, it created a sense of cosmic vastness, drawing visitors into a space that felt infinite — yet deeply personal.

The Intimacy of Infinity

“Our goal was to transform Hungarian cultural heritage into a living, emotional experience,” explains Bence Vági, the artistic director behind the concept. “We didn’t just want to show who we are — we wanted to create a moment of connection. In essence, we built a bridge between Hungary and Asia. And that bridge turned out to be the Hungarian folk song.” The connection is more than symbolic. The foundations of Hungarian folk music still carry echoes of Asia — the pentatonic scale, for instance, is a structural commonality between Hungarian and East Asian folk traditions.

As visitors stepped into the boundless, dark interior of the Zengő Dome, they were immersed in an audiovisual universe, where tiny points of light gave the sensation of floating in space. At the center of this universe stood a single Hungarian singer. Over the course of six months, twenty-one women vocalists took turns performing — every fifteen minutes, a new voice would sing a Hungarian folk song. The goal wasn’t just to listen: by the end, audiences were gently invited to hum along. “You sit in front of someone who actually comes from this faraway place, and they start teaching you a song in their native language,” says Vági. “To me, there’s no more intimate or beautiful experience than that.” Each folk song was presented in its traditional form, but the musical arrangement carried a cinematic twist. The emotionally charged, film score-like soundscape was composed by Edina "Mókus" Szirtes and István "Szalonna" Pál, blending authenticity with an atmospheric depth that pulled listeners further into the experience. Together, the spatial, sonic, and visual elements merged into a fully immersive installation. The audience didn’t just observe — they became part of the performance, drawn into the emotional orbit of the singers. Through light, sound, and shared voice, the Hungarian folk song became not just a cultural display, but a lived moment of connection.

The Ever-Cheerful Miska

Several countries opted for kawaii-style mascots — cute, cartoon-like characters with oversized eyes and rounded features, clearly inspired by Japanese pop culture. The Hungarian team, however, wanted something deeply rooted in national tradition. Creative duo Ördögh and Drozsnyik found their answer in the miskakancsó, a jovial, mustachioed ceramic wine jug that once sat on nearly every Hungarian family’s table. This folk object symbolizes joy and community: it was used to pour wine for guests, served at weddings, and even brought to sick relatives as a vessel for restorative drinks. Miska didn’t remain alone for long — he was soon joined by Mariska, his equally cheerful companion. Together, they serve as the friendly hosts of the Hungarian Pavilion, welcoming visitors with a smile. Near the stairway leading to the Miska Kitchen & Bar, the two mascots also entertain guests with fun facts and trivia about Hungary — adding charm, character, and a touch of playfulness to the experience.

Bubbles & Tokaj

If there’s one word that evokes Hungarian gastronomy across the globe — particularly in East Asia — it’s Tokaj. It’s no surprise, then, that the pavilion’s restaurant and wine bar, Miska Kitchen & Bar, revolves around Hungarian wine culture and native grape varieties. This is not only a key element of national branding, but also a strategic opportunity to expand Hungary’s wine export market. The ever-smiling Miska and Mariska bring bubbles to the party as well: Hungary’s invention, soda water, makes its appearance in the form of fröccs — the beloved wine spritzer — while fruit syrups offer a non-alcoholic option with the same effervescent charm. The gastronomic concept was developed by Balázs Csapody, owner of the renowned Kistücsök restaurant in Balatonszemes and president of the Pannon Gastronomic Academy. His menu highlights traditional Hungarian countryside flavors, avoiding over-stylized reinterpretations in favor of honest, updated presentations that suit the occasion. Dishes include paprika potatoes, goulash, duck liver, stuffed cabbage, Hortobágyi pancake, cottage cheese dumplings (túrógombóc), and Somlói galuska, Hungary’s iconic dessert.

Form + Function

Just like Olympic uniforms, the outfits worn by the staff of national pavilions tend to spark curiosity and attention before each world expo. Designing them is no small task: the garments must represent national style, meet practical needs, and reflect the cultural context of the host country. For 2025, the Hungarian uniforms were designed by Boglárka Bódis, founder of the fashion label Elysian, established in 2012. Bódis brought her signature aesthetic to Japan: sleek, playfully elegant pieces tailored specifically for the pavilion’s team. Given Osaka’s humid subtropical climate, the collection featured light, breathable fabrics in pale tones, complemented by practical hats. The restrained color palette and refined silhouettes respected Japanese preferences for more conservative style, while one bold detail added a distinctive touch: a vivid pop of red appeared in the accessories — a subtle yet memorable nod to the shared color of both the Hungarian and Japanese flags.

Did you enjoy this article? Order the 2025/1 issue of Hype&Hyper here!